I have been trying to think of an appropriate metaphor for what I have learned over the last two years. The best I could come up with is that we (current and budding public health professionals) have all been meandering in a dark room, feeling around for the one light switch that will completely illuminate the room. Once illuminated, all questions and answers will be clear, problems simple, and solutions actionable. As our hands explore the surfaces around us, we each feel what we think is *THE* light switch; so we get really excited, try to flip the switch and… the lights don’t come on. It turns out that there are actually a million different light switches in the room and there is a magic combination of on-switches and off-switches that will fully illuminate this room. As we all work on the switches around us – getting closer and closer to that magic combination – the room gets marginally brighter. From moment to moment the changes may seem imperceptible, but, over the long-term, the room gets brighter. Some switches add more brightness than others, some actually make the room darker, some require an impressive amount of time, energy, and resources to flip, and some switches affect other switches in unpredictable ways, but with everyone’s sustained effort the room continues to brighten.

I have been trying to think of an appropriate metaphor for what I have learned over the last two years. The best I could come up with is that we (current and budding public health professionals) have all been meandering in a dark room, feeling around for the one light switch that will completely illuminate the room. Once illuminated, all questions and answers will be clear, problems simple, and solutions actionable. As our hands explore the surfaces around us, we each feel what we think is *THE* light switch; so we get really excited, try to flip the switch and… the lights don’t come on. It turns out that there are actually a million different light switches in the room and there is a magic combination of on-switches and off-switches that will fully illuminate this room. As we all work on the switches around us – getting closer and closer to that magic combination – the room gets marginally brighter. From moment to moment the changes may seem imperceptible, but, over the long-term, the room gets brighter. Some switches add more brightness than others, some actually make the room darker, some require an impressive amount of time, energy, and resources to flip, and some switches affect other switches in unpredictable ways, but with everyone’s sustained effort the room continues to brighten.

The fact of the matter is this: after all these decades, the room is still somewhat dark, and there is no single switch that will fully illuminate the room, but, the net effect is such that our collective efforts have made the room a little less gloomy. And that, to me, means it is worth it and necessary to stay in the fight to illuminate the room, to keep working at it (to the degree that is possible while also maintaining wellness because #selfcareisimportant).

This was not what I expected to learn during my MPH. When applying, I was convinced that the MPH experience would equip me with all the skills necessary to be a part of the “team” to solve systemic issues contributing to the health inequities with which I am primarily concerned and result in a long fruitful career after which I would leave this world a little teeny tiny bit better than when I came into it. I was convinced that the faculty of my program had all the answers and for the low low price of tens of thousands of dollars they would share with me all of their secret solutions. I was convinced that I was entering a magical fairy land of public health amazingness and it was going to be the most intellectually-stimulating and passion-driven two years of my life.

Forgive my youthful naivete, if you will. As you may have guessed, things did not turn out quite as expected. In my first year, it quickly became clear that I was not going to learn how to solve the problems that consumed my thoughts. We frequently discussed the usual newsworthy contemporary public health problems (such as obesity, obesity, and more obesity, e-cigarettes, and [eventually] Ebola). We reviewed the historic successes of sanitation and vaccines, but learned little about how to “fix” some of today’s most tenuous public health issues – the ones that lay at the intersection of social norms, political leanings, and economic forces, and are further complicated by people’s multi-faceted identities (of which gender, sexuality, race, ethnicity, immigration status, English proficiency, and geography, are only but a few pieces).

Part of the reason we didn’t learn about the “right solution” or the “right answer” is that: (1) there is no one “right answer”, (2) we are still trying to figure out which problems are ours to solve – I lean towards an inclusive definition of what is “within scope” for public health, but not everyone agrees with that, (3) even the problems we have decided are within our purview are exceptionally complex and difficult to “solve”, and (4) we are never going to solve them if only those within the public health bubble are focused on and paying attention to these issues.

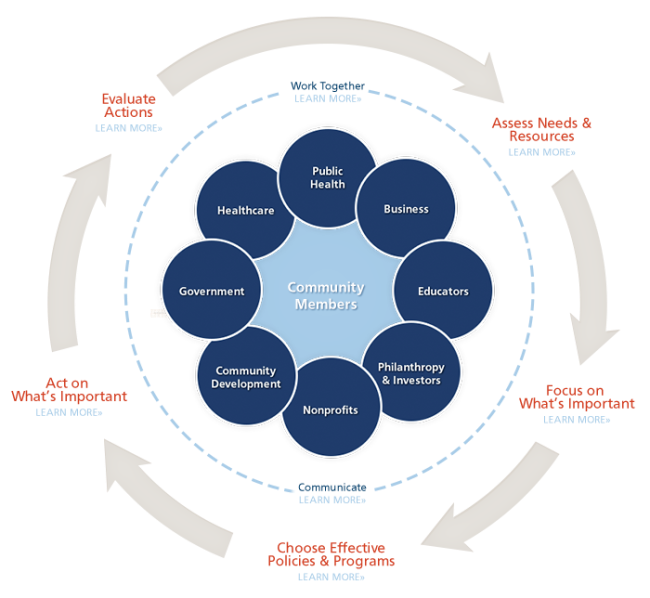

My social epidemiology professor made it most clear when she explained that the tools, resources, and knowledge we need to solve these problems exist in sectors outside public health. I took this to mean that until we fully acknowledge that fact and act in accordance with it (i.e. we disperse and work in other sectors to give them a health lens with which to frame their work and/or act as expert conveners who can collectively leverage the knowledge, power, and resources of other sectors) we are not going to get very far in cracking the really tough problems, especially the socially determined ones with which I am most concerned.

Okay, so the MPH experience didn’t give me the solution to the problem set as I saw it, but what did it give me? Stay Tuned for Part 2…